The Musical Nature of Consciousness

The connection between music and consciousness may not be just metaphorical - our earliest mechanisms of meaning-making are fundamentally musical.

Why do parents across every known culture instinctively sing lullabies to their newborns? Why has music, in all its diverse expressions, echoed through every corner of the planet and across the vast expanse of our cultural history? And why does music, when experienced under the influence of psychedelics, take on an almost unfathomable depth of new perceptions, meanings and experiences?

Could it be because the very foundation of consciousness itself might need to be recognised as inherently musical in nature?

Pondering these questions I started to formulate this as the new hypothesis that might shine light on each of these under the same single umbrella.

From the lenses of evolutionary theory, child development research and the neuroscience of learning and memory formation - this article will summarise some of the insights and reasonings that lead me to believe this to be not merely a poetic statement, but a rather literal one in fact.

The Musical Nature of Communication

When we talk about communication, we talk about meaning-making. More precisely, whatever route of communication is used (words, gestures, facial expressions, sounds, music, etc), this essentially concerns the conveying of a meaning - from the sender to the receiver.

For the majority of our evolutionary history humans communicated nonverbally through gestures, expressions, sounds, and music-like vocalizations. Like other animals still do. But one of the key distinctions between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom is the evolution of semantic, verbal language.

But before this, we used a so-called “proto-language” - a language that preceded the semantic, verbal language that evolved later. This non-verbal protolanguage of our early human ancestors is often argued to be the precursor to both music and language.

And for this reason, this protolanguage is sometimes referred to as a "musilanguage”, because it is hypothesised to have relied heavily on the use of musical vocal qualities such as melody, rhythm, tone-colour and pitch, to convey emotions, intentions, and social cues.

Thus, the way we communicated vocally with one another, for the last majority of our evolutionary history, was likely much more similar to music than speech.

And these musical qualities remain with us today. Some examples of primal musical remnants that are widespread, include vocal expressions such as laughter, crying, sexuality. And there are many more examples to give.

Many of such musical vocalisations that you find yourself making throughout any given day, are meaningful:

Evolutionary: i.e. your 1000th generation-old ancestors would likely understand their meaning;

Cross-culturally: i.e. any other culture with a foreign language would nevertherless likely still understand their meaning. And;

Ontologically: i.e. babies would likely understand their meaning.

Apart from our primal screams of joy, pleasure, despair and anger - We use musical qualities in our voice continuously to communicate our internal states, and to give a given emotional flavour to our words.

Basically, speech without musical qualities is devoid of subjectivity. We deploy changes in rhythm, tone and timbre to convey emotions, intentions, and social cues, beyond the mere symbolic reference of the words.

This is well illustrated by what is considered to be the first electrical speech synthesizer, VODER (Voice Operation DEmonstratoR), developed by Homer Dudley and presented in 1939:

Whereas for the opposite, when we remove semantic meaning entirely but keep the musical qualities, we end up with gibberish in the style of Pingu:

Or the glossolalia as expressed by Terence Mckenna, who interestingly hypothesised a significant role for psychedelics in the evolution of verbal language:

As allured to in previous paragraphs, both language and music most likely evolved as a shared system for emotional communication and social bonding. And we find strong support for this view from a neuroscience perspective too.

The brain regions, networks and processes involved in processing language or music, are in fact strikingly similar.

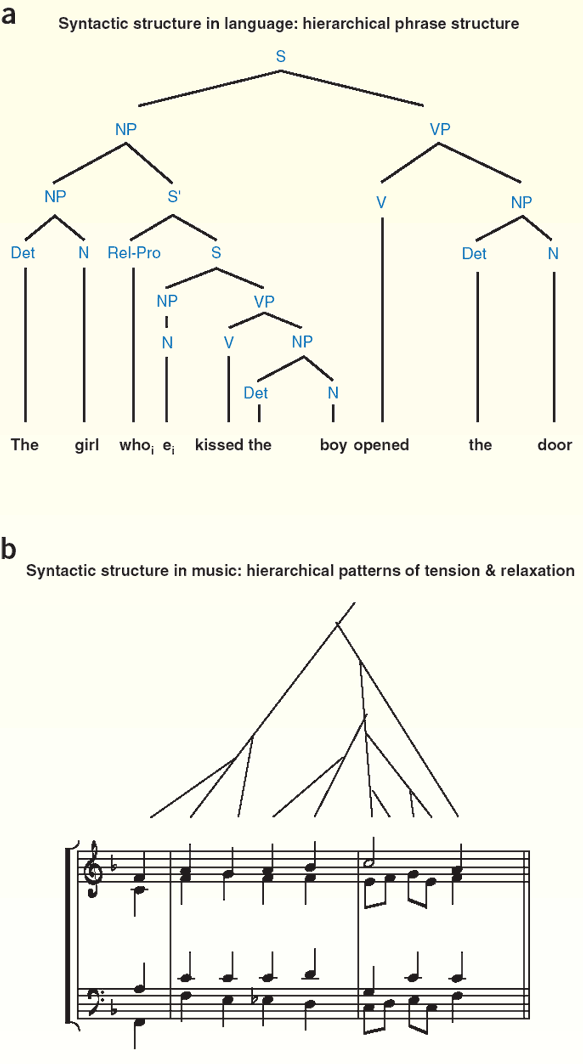

Both music and language are “sounds structured in time”, characterised by hierarchical syntactical frameworks and a diverse array of dynamic acoustic properties such as tonal modulations, rhythmic variations, and timbral shifts.

In “Music, Language and the Brain” by Anirudh Patel, Patel introduced the “Shared Syntactic Integration Resource Hypothesis” (SSIRH), where he explains that both musical and linguistic syntax rely on highly overlapping neural resources.

The argument for SSIRH is supported by a growing list of neuroimaging studies that show:

Auditory cortices are actively engaged in deciphering the acoustic properties of both language and music.

Regions implicated in syntactic processing, notably the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), are similarly recruited when parsing the temporal patterns inherent in both language and music.

Higher-order brain areas such as the insula, amygdala, and temporal lobes play critical roles in attributing emotional significance and meaning to both language and music.

Collectively, the consensus in the academic field currently leans towards viewing the cognitive and neural architectures for language and music not only to overlap significantly but to also share common evolutionary and developmental origins.

The Non-verbal Foundations of Mind

Although verbal language takes a central and dominant place in the lives of adulthood and modern culture, in child development it appears only at first around 12 months after birth. With more complex linguistic structures forming between ages 2-3, and a basic grasp of grammar emerging by age 5.

This is pretty important to recognise, because it means that non-verbal communication processes are fundamental to the earliest and most foundational developmental processes of children.

In fact, for infants, non-verbal communication is obviously the only source of meaning-making, even before birth.

These non-verbal sensory learnings in early childhood/infancy form the first learned mental building blocks for conceptual reasoning later in life. These ‘building blocks’ are often referred to by developmental psychologists as “Schemas” or “schemata’s” - originally introduced by Jean Piaget in 1923.

Schemas are defined as structured mental representations that organise knowledge and guide cognitive processing. They basically form a kind of implicit memory system that determines the ways in which our mind processes and gives meaning to our ongoing flux of life experiences.

In “The Foundations of Mind” Jean Mandler explains that conceptual development begins with an early, nonverbal system of "schemas", entirely derived from sensory and motor experiences.

Specifically, Mandler introduced the concept of "image-schemas", which are pre-linguistic, and provide a foundation for conceptual thought by capturing recurring patterns in experience, such as “containment”, “path-following”, and “support”.

One example of one of the earliest types of schema’s that researchers have been able to pinpoint the development of in childhood, is the capacity for children to differentiate between animate and inanimate when they are 4-6 months old.

The reason why I reference this concept here is for the following main point:

Unlike linguistic symbols, image-schemas are grounded in embodied perception, allowing infants to structure and interpret the world before acquiring formal language.

Only much later, after the formation of these fundamental processing pathways are well-established, will our mental models evolve to include the more sophisticated cognitive structures that include language and reasoning.

Importantly, these higher level models are constructed incrementally from infancy onwards, via a dynamic, experience-dependent learning process, and based upon (or with roots within one might also say) these ontologically ancient non-verbal schemas or memory systems.

And the more time progresses after the initial learning experience, the more the implicit schema takes dominance over the related explicit episodic dimension of the memory.

Image from Tompary et al 2020.

The Musical Origins of Being

What Mandler left out in her analysis is the fact that infants already built memory systems and schemas for many months before their eyes are opened to the visual dimensions of their world. Mandler's work instead is largely centered on visual and spatial representations as the basis for conceptual thought.

However, the neural circuitry for auditory perception in infants begins to develop quite early on in gestation, and is believed to mature (and be able to process audio sufficiently) when the infant is still unborn / in utero , 18-25 weeks old - correlating with infant’s capacity to recognise their mothers voice in numerous studies.

Researchers such as Sandra Trehub and colleagues provided many valuable insights in the innate sensitivity to musical elements such as pitch, rhythm, and melody in perinatal infants - suggesting that musical perception really should be seen as a fundamental aspect of human cognition, preceding verbal development, and preceding the formation of visuospatial “image-schema’s”.

As mentioned briefly before, infants begin to comprehend and form simple words only after around 12 months, and only develop more complex semantic structures by ages 2–3.

Our first relationships in life are essentially musical relationships. We are born in a musical reality at first.

As Daniel Stern helped us recognise so well, there is an essential role for non-verbal emotional attunement by parents to stimulate a healthy emotional learning environment for infants, based upon musical processes such as the use of motherese and expression of vitality forms as the foundation for this non-verbal form of communication that infants seem to be hardwired for to understand quickly.

The Musical Foundations of Mind

Daniel Stern also introduced the concept of “proto-arratives", referring to the dynamic and pre-verbal organization of experiences that infants develop through implicit learning. These “proto-narrative” are marked by musicality, affect and a temporal patterning, and form the foundation of an individual's meaning-making apparatus.

Therefore:

Not merely are we born first and foremost into a musical reality, but our very first memories - we can thus say without even being poetic- are largely musical memories.

The first internalised decision-trees of information processes formed within our infant brains, i.e. the foundational schemas we acquire in an experience-based implicit manner, have an inherent musical quality to them.

Not only are these initial schema-systems ontologically ancient, we need to realise that these models of meaning making occur around processes and phenomena that are most significant for the individual infant. They concern the ways we learn how to engage with the most intense existentially-charged tides of life:

How we regulate comfort vs pain, relaxation vs tension, satisfaction vs hunger, being in peace vs being in a state of terror, feeling safe vs feeling insecure, being in “heaven” vs being “hell”, when/how/with-what to attach vs detach, etc.

The most influential experiences that shape how we fundamentally perceive the world and our place within it are entirely non-verbal and predominantly musical.

In short, amongst the very first foundations of the mind of the developing infant are literally musical in nature. The resulting memory systems that continue to influence the qualities of all our subsequent life experiences have inherent musical qualities.

This is pretty mind-blowing. Not only intellectually, but because this has serious relevance to how we conceptualise and develop more effective psychological healing modalities.

Perhaps music resonates so profoundly across so many states because it reminds us of a time when meaning was felt and lived, rather than spoken—before the layers of conceptualization and interpretation became our default way of relating

Fascinating connections here. Seems that there is a whole unexplored universe related to a musical interpretation of attachment systems and how humans experience growth/development/transformation