What Makes Music Therapeutic? (2)

Embedded in music we find an inherent intersubjective dimension, a reflective field in which we can experience and develop a sense of self.

This article is the continuation of the series introducing distinct therapeutic functions of music and What Makes Music Therapeutic?

Prelude

At some point in our human history we learned that certain structures of sound could reliably evoke certain experiences.

Like any transformative technology, this freshly acquired power soon found its way into a growing diversity of rituals and activities, across the entire globe, for countless generations and up till today.

Music-making became a practice of evoking the spirit or essence of a phenomenon, place, animal or person. It became an art of evoking worlds. And by living and navigating those worlds together, it enabled a deeper and new kind of anchoring of individual minds together, into a more collective identity and reality.

As stated in the previous part, music is exceptionally effective in this because it does not merely work by symbolically representing, but by (re)creating subjective experiences.

It might be hard for us to fully grasp the transformative impact that music hereby had historically. The reverence we once held for music since it first emerged and developed within our earliest communities,

It feels reasonable to suspect that for many of us, this historical veneration for music, and the immediacy and magnitude of it’s impact, got muddled or even lost. Somehow and somewhere. It is partially for this reason that I believe that when we intend to work with music therapeutically, a certain re-calibration in our relating to music is often needed.

One part of this is knowledge. But another part is to ignite, inspire and re-establish some of that original archaic reverence. And alongside, a renewed openness and a deepened capacity for listening more actively and deeply.

Not to idealise music. Not to assign it some sort of magical-salvation-like status that has the potential to heal everything and everyone. But to understand it, respect it and to be able to put it in the right place. Knowing when not to play music in therapy, is at least be as important.

In this line, more broadly exploring music’s unique capacity to “evoke worlds” sits at the heart of this writing. More specifically, and beyond this poetic notion, here we will start by looking at music through the concepts of intersubjectivity, borrowing from both neuroscience, developmental psychology and psychodynamic theory.

As previously mentioned, introducing these series of concepts is not intended to be comprehensive or definitive by themselves. Instead, with each concept I aim to highlight a particular aspect or unique quality of music. Each represents a distinct lens through which we can view music’s therapeutic potential from a certain angle and resolution. While put together, they are intended to lead to a perspective that is heuristic and integrative.

This piece was one of my first personal introductions into “Yoiking”: a traditional vocal art form of the Sámi people of northern Scandinavia. Yoiking is believed to be one of Europe's oldest surviving shamanic musical traditions. Originating as an animistic practice, each yoik is a sonic embodiment of a person, animal, or place. It is meant not to describe, but to actually evoke its essence. Traditionally, yoiks are performed without instruments, in a circular, repetitive, and trance-inducing style, often used in storytelling, healing, or to maintain connection with nature and ancestral memory.

Defining Intersubjectivity

The term intersubjectivity was first introduced by Edmund Husserl and refers to the dynamic process of sharing and synchronising subjective experiences and meanings between individuals. This concept has become foundational across various disciplines from phenomenology to developmental psychology and psychotherapy.

Intersubjectivity should not be seen as a process of merely being present with someone else (i.e. someone else’s subjective reality). Neither only as the perceiving of this. Instead, intersubjectivity essentially concerns an active participation in creating and sharing subjective experiences with another.

Intersubjectivity is not confined to abstract cognitive or linguistic representations, but instead is fully embodied, directly-felt and phenomenologically real to all individuals involved.

The Centrality of Intersubjectivity In Human Development

From a neuroscience perspective, this understanding is central to Vittorio Gallese’s notion of a "Shared Manifold of Intersubjectivity", which he defined as a multimodal space where people embody others' senses, emotions, intentions, and actions.

This process is argued to stimulate a recognition of others as beings like ourselves, but without collapsing or losing the self into the other. Instead, this sense of otherness is seen as a necessary criteria for the development of identity during our development.

It is in this frictional field of “otherness” that we experience ourselves as separate from the other.

Intersubjectivity evolved as an important human adaptation. It enabled the cooperation of complex, fine-tuned social activities such as child-rearing, hunting or warding off predators. Humans were able to develop intersubjectivity so extensively because it builds upon the evolution of brain systems such as mirror neurons and limbic regions.

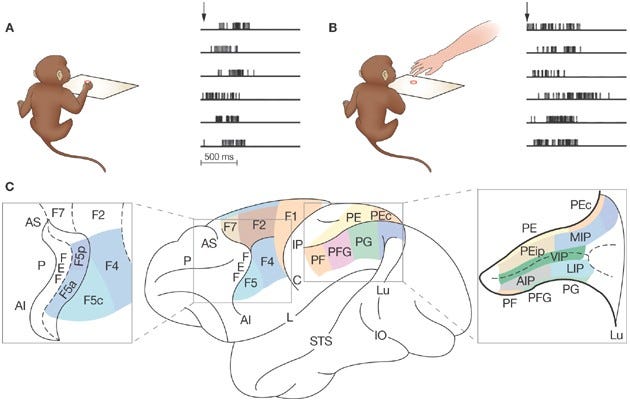

The mirror neuron system was discovered in the early 1990s by a team of Italian neuroscientists led by Giacomo Rizzolatti. While studying neuronal activity in the motor cortex of macaque monkeys, they found that certain neurons activated both when the monkey performed an action (e.g., grasping an object) and when it observed the same action performed by another. This system is thought to integrate action perception and execution, allowing individuals to understand others' actions and emotions directly, without relying on higher-order cognitive processes (image taken from Rizzolatti et al 2009)

The Centrality of Musicality In Developing Intersubjectivity

One key point to recognise here as my line of reasoning progresses, is the remarkable interconnectedness between the developmental timeline of intersubjectivity and the primacy of pre-linguistic musicality along that timeline:

Intersubjectivity in Evolution: Intersubjectivity evolved long before language and is therefore understood as being rooted primarily in non-verbal modes of communication.

Intersubjectivity in Child Development: Both the mirror neuron system and music perception are functionally present in early infancy and engaged extensively during the key developmental periods in which intersubjectivity is developed.

Starting with primary intersubjectivity (up to ~6 months post-birth), infants actively engage in face-to-face interactions, gazing and musical vocalizations. Subsequently, within a period of approximately 6-18 months post-birth (known as secondary intersubjectivity) , the capacity to recognise another’s actions & theory of mind reaches a gradual maturation.

Daniel Stern pioneered and highlighting the central role of musical vocalisations or “motherese”, and what he termed “forms of vitality”. The dynamic, rhythmic, and melodic modulations in the caregiver’s voice and movement are widely understood in the field as essential communicative properties that impact the infant’s sense of self.

The Musical Foundations of Self

It is during these early developmental periods, characterised by heightened neuroplasticity and steep learning curves, that also our most significant emotional attachments are made.

These memory systems are therefore non-verbal, pre-linguistic and the infant utilises “communicative musicality“ as a primary means to establish a"shared manifold of intersubjectivity” with significant caregivers. Our most foundational mechanisms for intersubjectivity and emotion-regulation are assimilated in implicit memory.

“Infants are not isolated minds, but born to share emotion and intentions in musical narratives of companionship.”

- Trevarthen (2002)

These musical interactions in infancy lay the groundwork for what Daniel Stern refers to as proto-narratives envelopes: pre-verbal, affectively-charged experiential patterns that the infant internalises long before linguistic memory develops.

One important consequence of this, is that our most foundational mechanisms for intersubjectivity, are thus encoded to follow a logic that is inherently musical in nature. Our first attachment figures are perceived and internalised, quite literally as musical entities.

Music is a Process of Evoking Intersubjectivity

“To listen to music is to trace the virtual movements and intentions of an absent other.”

- Clarke E.F

What I am proposing here, is that intersubjectivity seems inherently musical, and that music seems inherently intersubjective.

Music interacts upon foundational schema’s that originate (at least to a strong degree) in critical developmental periods. These internalised proto-narratives are defined by rich musicality and gesture, and form foundational templates for how the person will experience connection, attachment, intimacy, emotional coherence and meaning in relationships.

These early proto-narratives are not musical in a symbolical sense, but in a literal and structural sense. They are hardwired neuronal networks representing the temporal and acoustic contours of a musical narrative.

These foundational schemas influence what subjective experiences emerge in response to musical qualities alike. It seems plausible that for this reason subsequent experiences with music will retain and evoke a fundamental intersubjective quality, representative of the musical qualities that characterised those initial developmental experiences of intersubjectivity.

Although controlled experiments to test these hypotheses in humans would be complex but not impossible, there is various indirect evidence that supports this hypothesis.

Even when we are listening alone, or when the piece is entirely instrumental, music is often experienced to have a social intentionality embedded within. People actively seek music in order to reduce feelings of loneliness. Music can reliably evoke a sense of consolation, a sense of an “other” , a sense of relatedness, and is not uncommonly described anthropomorphically.

Within this manifold of intersubjectivity, despite it being entirely musical and devoid of real humans, music can evoke the sensation of an “other”. Although this sensation may be imagined, it is directly felt and realistic.

Interestingly, within psychedelic therapy research, a related phenomenon has been observed and reported. It is common for music to be experienced as a source for “holding” or “caring”, as well as the exact opposite, for music to be experienced as for example abusive, unfriendly or unreliable.

Central in these findings together is notion of an “other” experienced within the music during psychedelic therapy sessions, and for this music to be personified in various degrees.

This is illustrated nicely by some of the quotes selected below

These first quotes are taken from a recent study by Dwyer et al (2025), who observed music to be commonly experienced as a “sentient actor” with “own intentions” and an “authority within the participant’s lifeworld”:

“The music was its own entity, and it was trying to kill me “

“I felt very connected to the music and the music felt alive and like it had a life of its own and I was part of it”

Henryck Gorecki’s “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” proved polarising in clinical trials I selected this music for in the past. I shared some reasons partially here, but there are other valid explanations yet to be discussed as part of this current exploration.

The findings of Dwyer align with some of my research on the matter, where I noted that it was common for music to be perceived as a source of“guidance” or “misguidance”. Some patients I interviewed also experience music as having or being an autonomous “other”:

“I did feel as if I was being held. The music took my thinking and my experience to uncomfortable places, but I was kind of reassured in the experience”

“There was something there that meant that, you know, ‘I’m going to take you on a ride here, but I promise I won’t abandon you’. That seemed to be what the music was saying to me.”

“ I just felt as if I was being manipulated, being duped almost. The music was playing a trick with me, you know, sort of giving me a false sense of security.”

“That was profound, because it was as though there was somebody orchestrating that, somebody manipulating that, you know, not in a good way.”

Taken together, in what ways do these kind of “intersubjective” musical experiences contribute to transformative therapeutic experiences ? What is the therapeutic relevance of experiencing intersubjectivity in music ?

Though often interpreted as a warning against vanity, the greek myth of Narcissus also evokes the idea of self-recognition as both a curse and a blessing. A first mirror moment where the self sees itself, creating a split that births subjectivity. A painful but necessary encounter, the realization that the "I" is a separate object that can be perceived.

Reflections and Postlude

Synthesising this exploration and concluding this part, I like to emphasise that I do not suggest to believe that adult musical experiences are entirely determined by musical experiences in infancy. I understand very well that this is influenced by a complex range of interacting factors.

I also recognise that early life experiences can be enriched, reshaped or overwritten by subsequent experiences in life. Especially during moments of heightened emotional or cognitive intensity, or pharmacological modulation. And these can subsequently change our perceptions of music too.

But I do strongly suspect that communicative musicality during the formation of intersubjectivity in infancy, plays an influencing role in our relationship to music later in life.

But, importantly: Independently of how certain life experiences may impact music experiences in adult life, there are strong grounds to view the process of experiencing music as inherently intersubjective. This is one key point I want to invite us to bring along on board as we continue to explore these questions.

Music can be perceived as sentient and social. As a source for solace and support. A climate of “unconditional positive regard” where one can feel held and seen .

Although these points address the central inquiry of this article somewhat, ending the exploration right here already would be pretty premature.

It is clear that music can evoke experiences across the entire spectrum of social valence. Thus, when music can become such a living entity, capable to both hold or abandon, support or abuse, soothe or overwhelm the patient - what does this mean? Through what frameworks might we understand the significance these have to therapeutic work? And from that, to know how to work with these ?

Well, “the self is created in the crucible of intersubjective experience”, Daniel Stern once said. And he might have responded something similar in response to the above questions.

To have our self mirrored back to us, inside of the experience of a significant other. This process is in fact amongst our earliest modes of learning and constructing a self.

The therapeutic processes of music-listening seem to be at least partially characterised by a comparable mirroring process. An experiencing of reflections of self and other.

Active listening as described by Carl Rogers, is essentially a practice of intersubjectivity. And actively listening to music essentially equals an active listening to the self.

The next parts will expand upon these notions through the lens of Musical (re)enactment and music’s capacity to evoke immersive worlds. These worlds can function as Holding Environments, offering Transformational Objects through which a coherent and integrated sense of self can be constructed.

This is a wonderful overview of the cognitive and social impact of music and sound. True, music often creates a shared experience, as in a concert setting or in religious services. Yet, everyone experiences and processes the music from their own learned perspective. So for instance, a happy summer song like “Hot Fun in the Summertime” may evoke happy feelings of carefree days for some. For others, that song could evoke feelings of loneliness and sadness if their life experience during the time that this song was everywhere was negative.

One aspect that you may have covered or are yet to cover would be the physical aspect of vibration on our human physiology. Composers organize sound, and thus vibration, to evoke feelings but the physical vibrations cause the listener to “feel” something simply by resonating with the frequency of the music. We are resonant beings. Everything in our world is vibrating at frequencies. Subjecting the environment to frequencies can invoke physical change, and in humans it is said that feelings and emotions are a mental reaction to physical sensations. I point to the tests of Tesla with frequencies and vibration. This salt example illustrates an instance of this phenomenon.

https://youtube.com/shorts/0tBx_qqK19c?si=uTwcrmN3ms_gRcfC

Great discussion. Thanks for sharing your knowledge. I’ll be following.

Loving this series, Mendel.

I find myself thinking about how recorded music’s defining feature—repeatability—allows us to return to an exact emotional contour, a known landscape, a feeling we can summon on demand. That repeatability is part of its magic. BUT it also reveals a paradox: the same qualities that make recorded music comforting can later become constraining.

If someone’s early life was marked by inconsistent care—abandonment, neglect, or the feeling of “not enough”—recorded music can become a kind of prosthetic attachment. It provides a reliably attuned emotional presence, available when needed.

I would never deny the utility of this at certain times. As a teenager, I had songs I returned to compulsively. In the same way certain drugs provide a predictable internal experience, music offered reliable access to comfort, pleasure, and structure.

That is, until it didn’t. Over time, the very thing that once brought me joy began to feel flat, or even alien. It no longer matched who I was becoming.

This is the shadow side of repeatability. Once we’ve undergone significant psychological change, the static nature of recorded music might begin to grate. A song might become boring, irrelevant, or even cringeworthy—not because it changed, but because WE did.

Engaging with recorded music in this way can function like a transitional object—similar to a child’s favorite blanket. It provides continuity in times of internal chaos. But like all transitional objects, its purpose is temporary.

Live, adaptive or improvised music that is responsive and co-created, offers a different kind of psychological utility. It resembles the qualities of a securely-attuned other: able to sense and respond, to change with you in real time, to go

beyond comfort and pleasure, and to make space for novelty, awe, and transformation.

As the person develops into a larger sense of self, the musical container can grow and adapt to reflect their own inner transformation.